At Hollis + Miller, co-creation is at the heart of everything we do. In all aspects of our work, we aim to learn from the diverse voices of varied experts. Despite being the end users of new learning environments, students are not always invited to participate in co-creation in a meaningful way. As active participants in their own educational experiences, students bring a perspective to help fill gaps in the design process. In fact, opportunities to co-create may be especially valuable to learners, as student voice is correlated with positive engagement and a sense of belonging1,2.

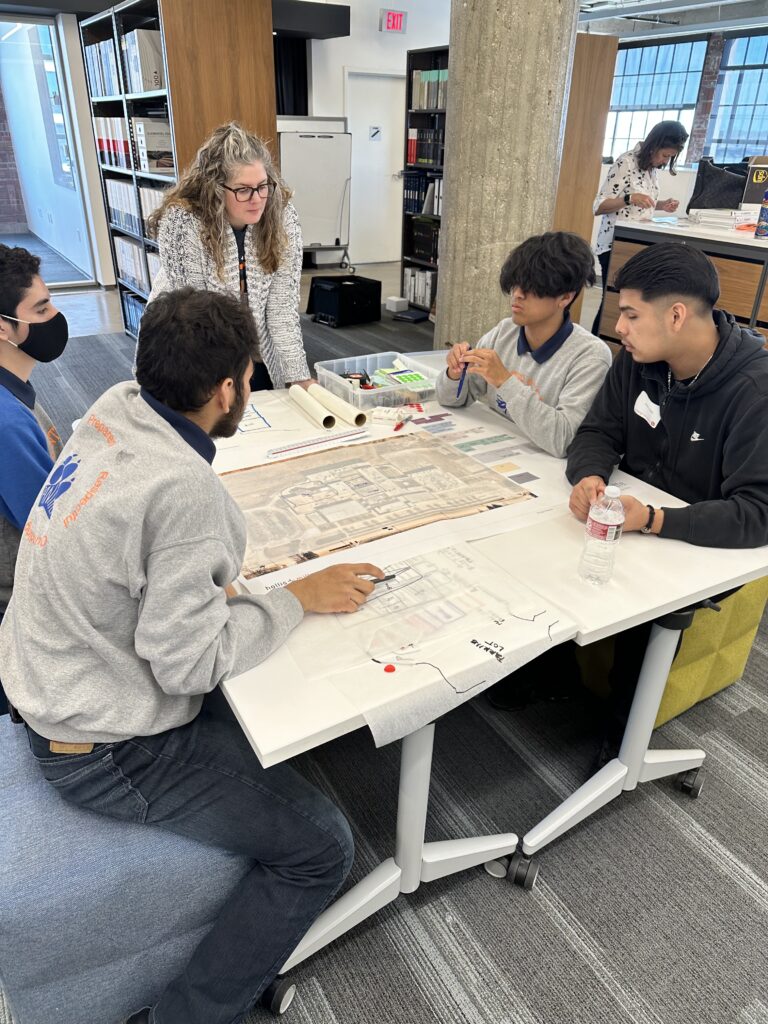

Approaches to student involvement can range from stakeholder engagement activities like surveys, focus groups, and visioning exercises, which occur during design, to more hands-on opportunities for choice and input once the building is in use. While our engagement tends to focus on students in middle school and above, these approaches may vary by learning level and individual student needs.

The benefits of including students as stakeholders in the design process extend beyond the facility’s outcome. This type of engagement will not only allow designers to respond to a more holistic understanding of the school’s needs and desires, but it also bolsters students’ academic experience. Research shows that students who believe they have a voice in school are more likely to experience self-worth, purpose, and academic engagement and motivation1. Likewise, at schools where students believe their feedback is acted upon, students boast better grades and attendance, as well as lower rates of chronic absenteeism2.

The benefits of including students as stakeholders in the design process extend beyond the facility’s outcome. This type of engagement will not only allow designers to respond to a more holistic understanding of the school’s needs and desires, but it also bolsters students’ academic experience. Research shows that students who believe they have a voice in school are more likely to experience self-worth, purpose, and academic engagement and motivation1. Likewise, at schools where students believe their feedback is acted upon, students boast better grades and attendance, as well as lower rates of chronic absenteeism2.

Students seem to recognize this implicitly, often expressing the importance of sharing their opinions and being heard.

The positive effects on student engagement are correlated not just with students using their voice, but with their belief they have been heard. Some research even suggests eliciting student voice without action can be damaging, as it leads to students feeling disempowered3.

To ensure students can be heard in the design process, designers and educators might consider the following strategies with middle and high school students:

Opportunities for student voice aren’t confined to the design of a new educational environment. In daily practice, flexible and adaptable environments can honor student autonomy – affording flexibility through physical elements like unique spatial opportunities and varied furniture options, or through intangible elements like a teacher’s approach to student choice in the classroom.

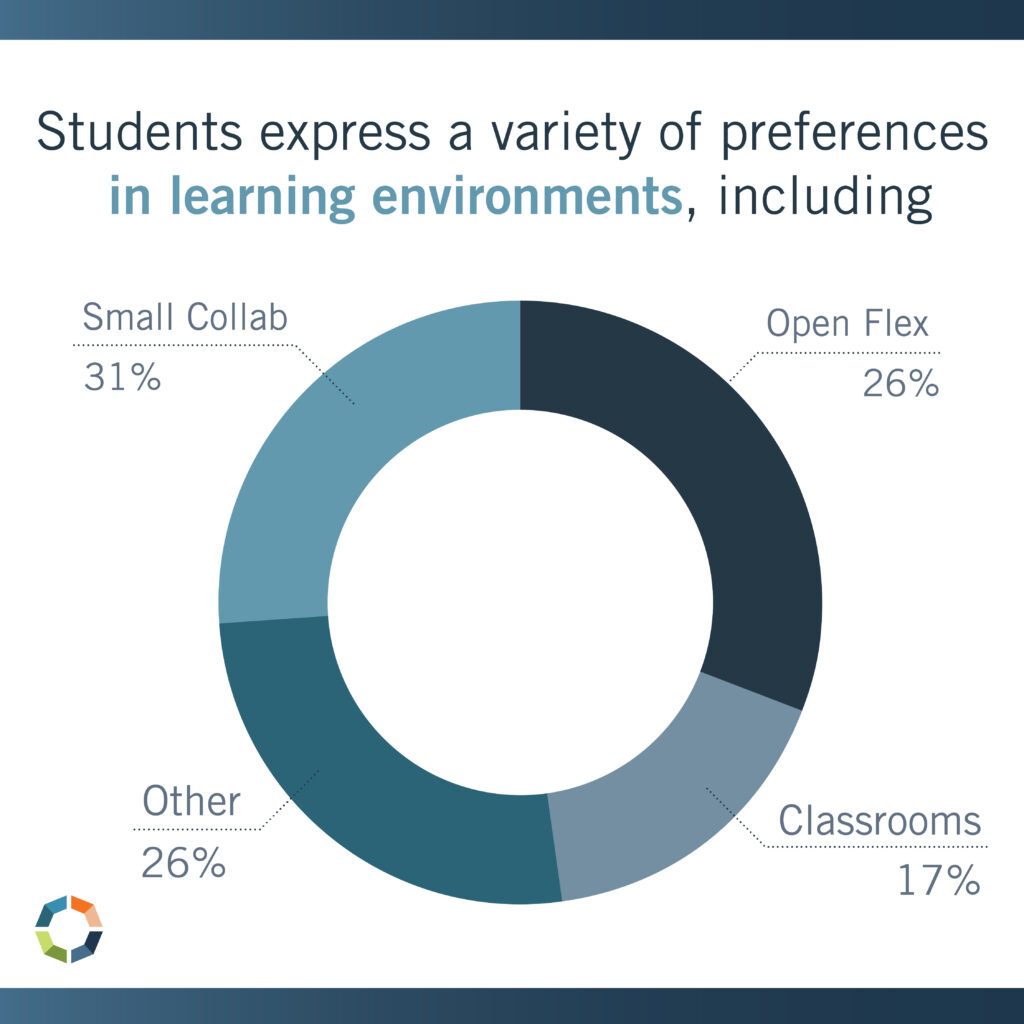

Recent post-occupancy surveys with middle and high school students revealed varied preferences for learning environments and approaches. When asked where in the facility they would choose to complete an assignment, students describe a variety of spatial types, including small and enclosed focus spaces as well as large and open flex spaces.

A broader approach may also support student voice and choice by allowing students to be co-creators in their curriculum and school operations. In one case study, Vista USD in southern California saw success in meaningfully engaging student ambassadors as stakeholders and co-designers of curriculum4. Prior to this program, students described their school experience with words like irrelevant, controlled, and boring, compared to five years after the implementation of this program, when words like fun, awesome, and amazing became most common.

To promote student autonomy in daily learning, designers and educators might consider the following strategies with middle and high school students:

By providing learning environments that offer students the opportunity to learn in the best way for them as individuals, and implementing teaching approaches that allow students to exercise choice in this way, students will have greater autonomy and reap the rewards of exercising voice and choice. Whether it’s through a collaborative design process as a facility is being updated, or through daily opportunities in an existing classroom, finding ways to include students as co-creators in their learning experiences promotes improved engagement and belongingness in the classroom and schoolwide.

Research Support

Share this post:

References

1: Quaglia Institute for School Voice and Aspirations. 2016. School voice report. https://quagliainstitute.org/dmsView/School_Voice_Report_2016

2: Kahne, J., Bowyer, B., Marshall, J., & Hodgin, E. (2022). Is responsiveness to student voice related to academic outcomes? Strengthening the rationale for student voice in school reform. American Journal of Education, 128(3), 389-415.

3: Mitra, D. (2018). Student voice in secondary schools: The possibility for deeper change. Journal of Educational Administration, 56(1), 473-487.

4: Allard, N. (2022). Students as stakeholders and co-designers. Next Generation Learning Challenges. Retrieved June 24, 2025 from https://www.nextgenlearning.org/articles/students-as-stakeholders-and-co-designers